Over a hundred years ago another major pandemic raged throughout the world.

By Bruce Doorly

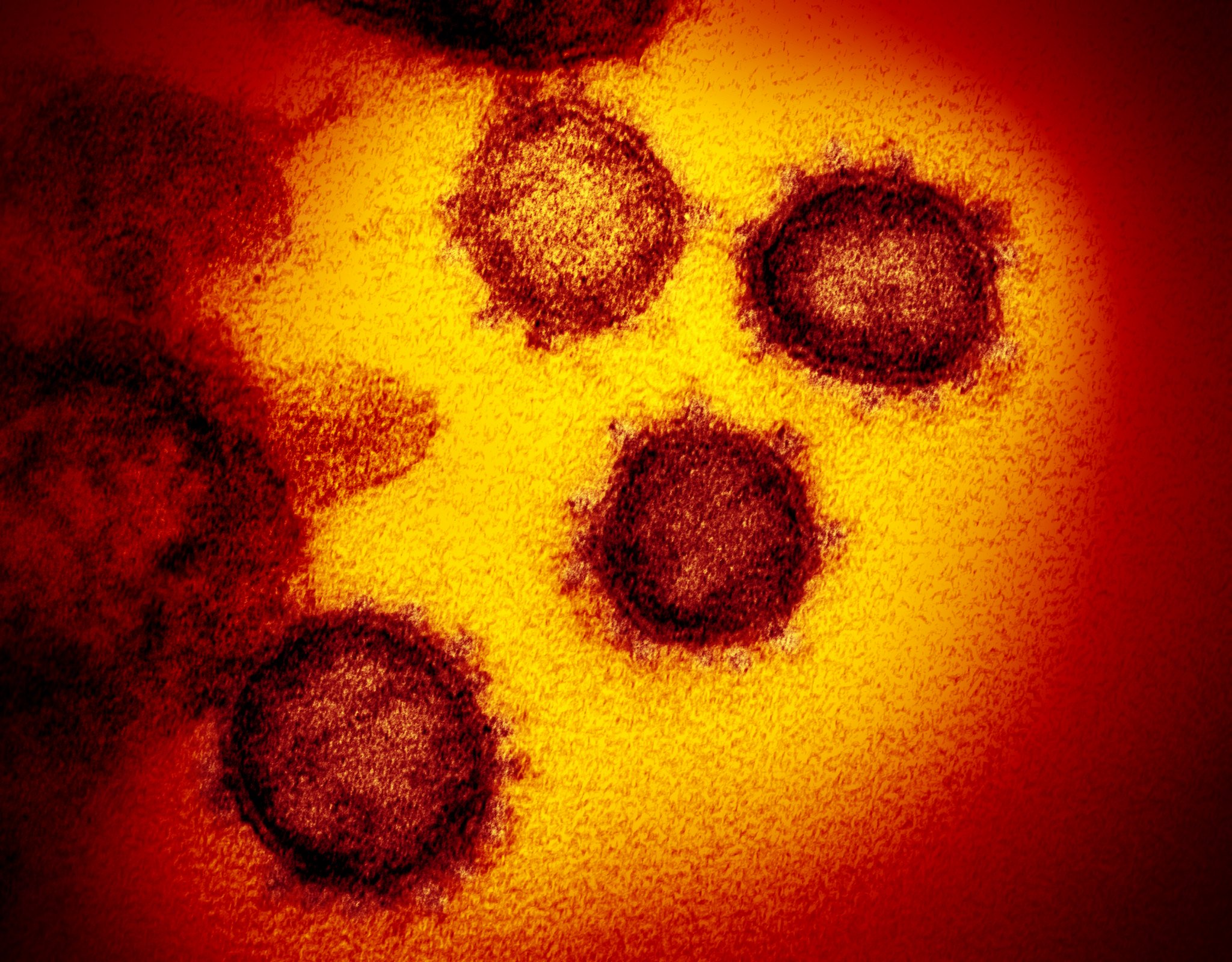

At the time of this writing globally almost three million people have been infected and over two hundred thousand have died. In the United States, almost a million have been infected and over fifty thousand have died.

From an economic point of view, millions have lost their jobs, thousands of businesses could face bankruptcy, and a recession is a certainty, with a depression a very strong possibility. Anxiety is high everywhere as nothing like this has ever happened in modern times.

It was often called the Spanish Flu. In the United States the death toll was around 675,000.

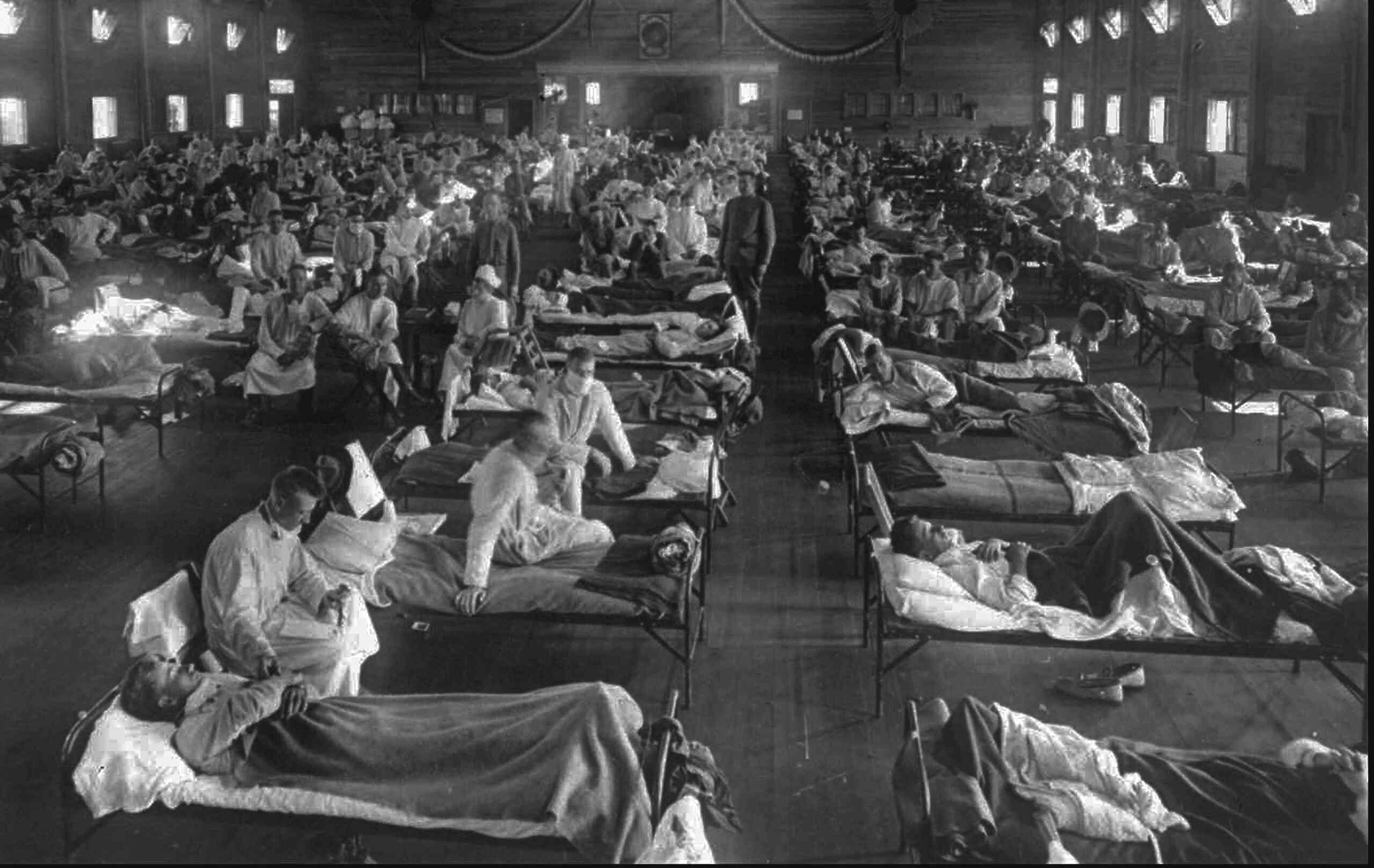

But after the first wave of the flu, another more deadly strain of the virus struck beginning in September. It spread quickly throughout the globe. The reasons for this spread was that the virus was highly contagious and it was during wartime. World War I was raging at the time. Troops that were huddled close together in their barracks caused a rapid spread of the disease. Then the infected soldiers traveled all over further spreading the infection.

The speed with which the disease often killed was as shocking as the number of people that it affected. People who seemed perfectly healthy in the morning could be dead by night.

Ironically, it hit the strongest and healthiest age group, as those in their twenties and thirties had the highest rates of mortality.

Cures seemed to be non-existent. Once one had the disease, all you could do was pray that you would recover.

Undertakers ran out of caskets. Many actually thought the world was coming to an end.

Former Raritan Mayor Jo-Ann Liptak recalls that her mother (who lived through the pandemic) told her that during the peak of the epidemic (October 1918) that there was a funeral almost every day in Raritan.

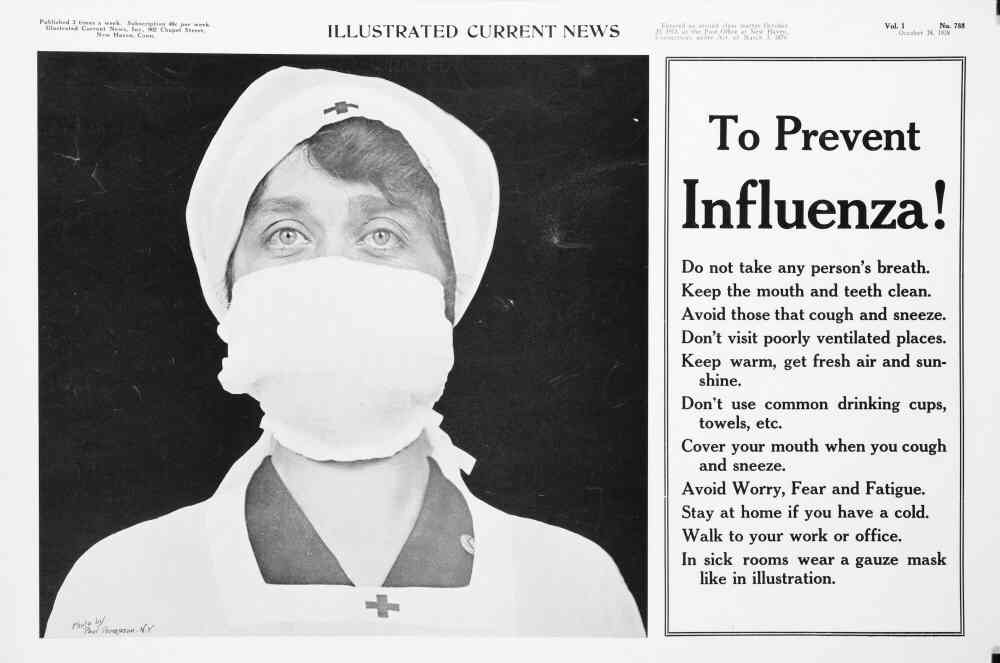

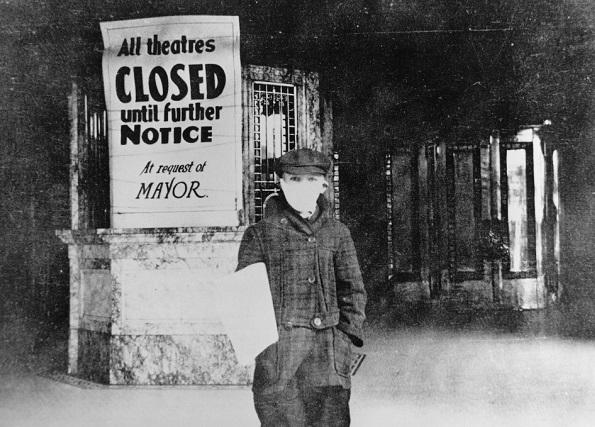

The only defense was not to get the virus. Simply avoid other people. Person-to-person contact needed to be greatly reduced. The government closed all schools, theatres, bars, and prohibited any public gathering.

The two Raritan schools the Primary School (located where the Municipal Building is today), and the Intermediate School (today that building is called First Growth Plaza), would suspend classes. No doubt the newly opened hang out for kids The Candy Kitchen (where the The Raritan Music Store is today) would have been closed.

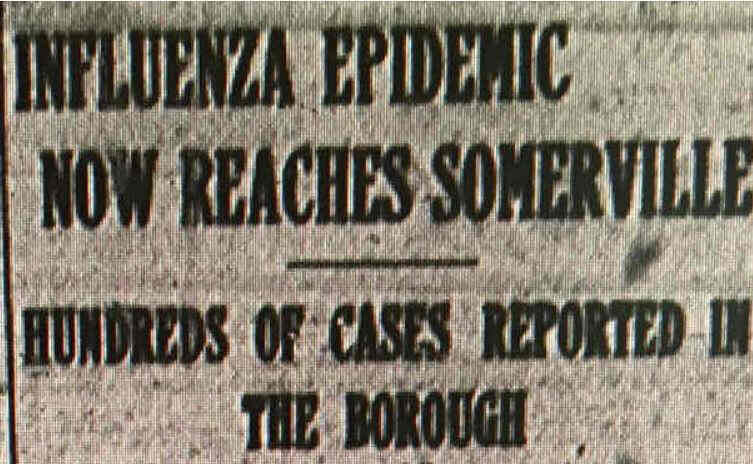

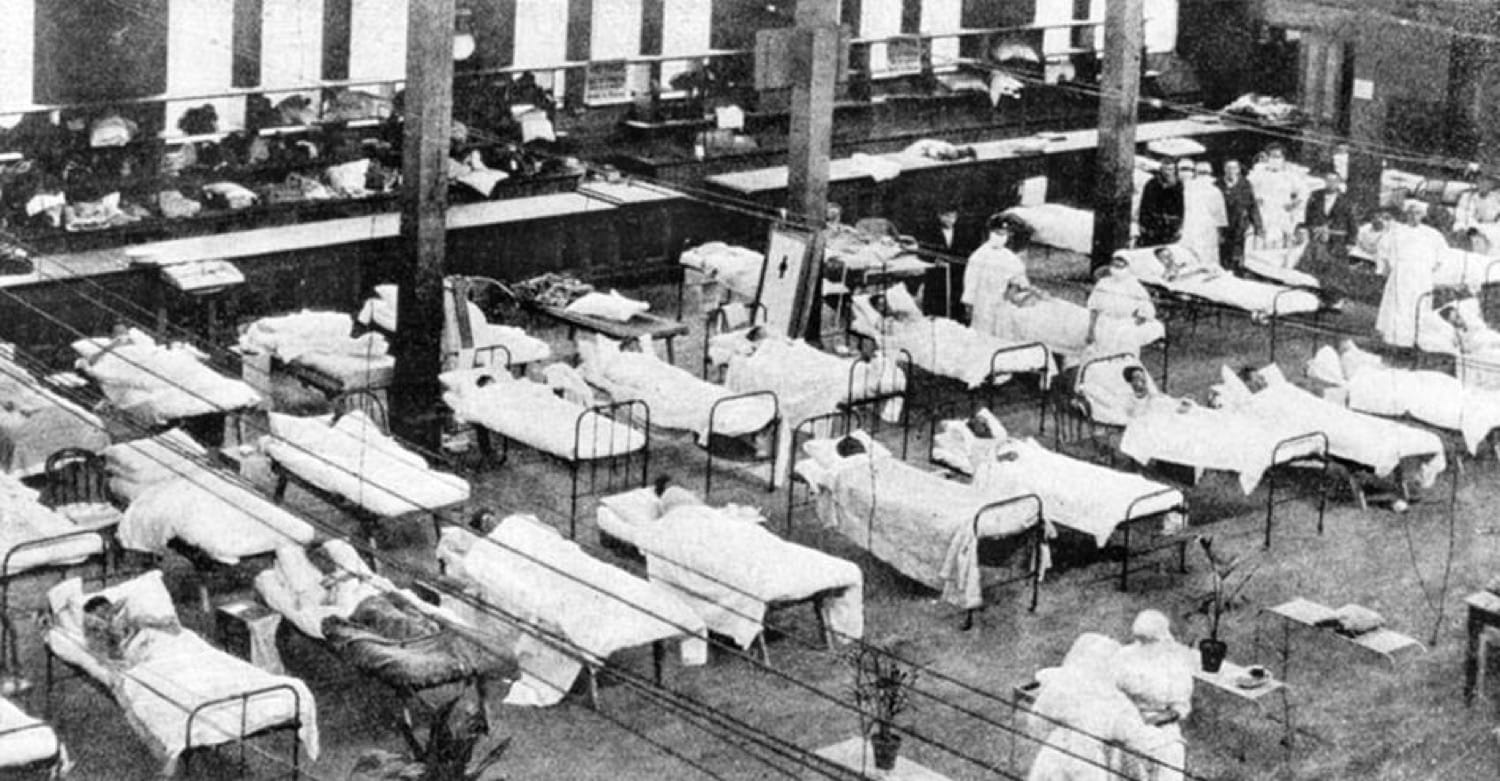

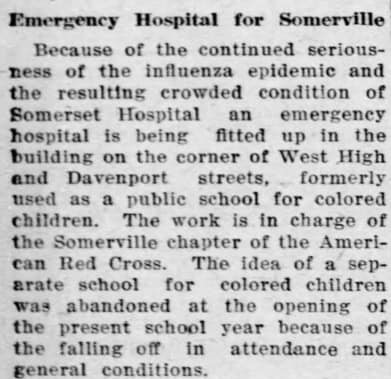

A secondary hospital for the overflow of patients was setup in a vacant school building at the corner of Davenport and West High Street in Somerville. Doctors and nurses were in very short supply due to the large number of cases and because one quarter of them were overseas aiding our soldiers fighting the war.

Mercifully the number of flu cases subsided in November and continued to decline dramatically in the next few months. The horror of it all would leave survivors to not want to talk about those horrible times. Many history books barely mention this pandemic.

The shutdown of public places, people avoiding each other, (today called social distancing), the overwhelmed hospitals and shortage of healthcare workers.

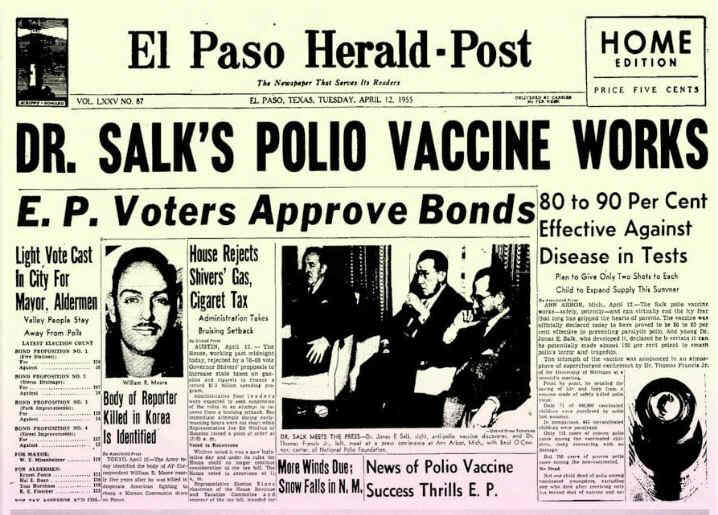

Indeed, mankind has chalked up many impressive victories against once formidable diseases. But our battle against the virus has yet to be won. This nasty little killer has just one purpose, to infect and multiply. First it infects an individual, then multiplies inside the body, and then tries (and often succeeds) to move to infect another.

At present time our best hope to stay safe when he strikes is to avoid him (by staying away from others), same as it was in 1918.