He was killed on Iwo Jima on February 19th, 1945

They are From Raritan's Hero - the John Basilone Story

The Japanese prepared for the battle for months. They built what James Bradley described in Flags of Our Fathers as “the most ingenious fortress in the history of warfare… (Japanese commander) Kuribayashi transformed Iwo Jima into the equivalent of one huge blockhouse”. Practically a city for the 20,000 Japanese soldiers was constructed underground. Expert mining engineers had made a system of caves, tunnels, meeting rooms, and communication centers. Some parts had electricity, others had fuel lamps. The underground tunnels had multiple levels, some as deep as 75 feet.

At the entrances on the surface, they constructed many firing positions called blockhouses that were reinforced with steel and concrete. These blockhouses were well hidden and well positioned to allow them easy firing at the soon to arrive Americans. Many blockhouses had multiple entrances.

Three days before the invasion on Iwo Jima saw an even more intense bombing campaign. However, as was later learned, the large majority of the Japanese were underground, hence they, with their equipment, had survived the most intense bombing in military history.

The soldiers wondered quietly to themselves, how will I hold up when the bullets and bombs start flying at us, will I let my buddies down, will I live or die ?

The day before the attack, February 18th, 1945, a serious tone was taken on by the men. All joking had ended. Nearly all the men attended one last religious service.

The Iwo Jima Invasion Begins

On the morning of the attack, the naval bombardment was so intense that the view of the island was partially obscured. Flames and debris shot high in the air. The noise and the bombing was escribed by one soldier as indescribable. While waiting in the transport vehicles some Marines hoped this final bombing would allow them to take the island with little resistance. However, these Japanese warriors were well dug in and heavily armed. There were 22,000 of them, and almost all were prepared to die in the upcoming battle.

The U.S. bombing stopped only minutes before the first U.S. invasion force landed on the beach at 9:05 AM. John Basilone’s group landed around 9:30 AM. They were surprised to find little opposition. They wondered “where were the Japanese ?” Had the bombing wiped out the enemy ? The Marines got up on the beach and noticed that their feet could barely move in the soft black volcanic sand. For one hour, the U.S. was able to get their transports up to the beach and unload the men without major resistance. Then, with the beach crowded with U.S. soldiers, the Japanese began their counter attack. Suddenly the Japanese from their hidden blockhouses began firing away at the exposed U.S. troops. This was their planned strategy. Hold off from firing immediately, then when there were thousands of U.S. soldiers grouped together on the beach, start blasting them. An estimated two thousand Japanese were gunning down the American forces. They fired everything from machine guns to heavy artillery shells.

Many of the Japanese strong positions were in the 550 foot Mount Suribachi. This allowed them to easily pick off the “sitting duck” Marines, who had no cover and very little footing on the beach. The Marines tried to dig into the sand to provide cover, but the volcanic sand was just too soft. For each shovel they dug out, it seemed two shovels filled back in the hole. The Marines were getting annihilated. The noise and the carnage was everywhere. Survivors later wondered how anyone survived the initial Japanese barrage. The U.S. forces were on the beach, but they had little or no cover, were still disorganized, and had not yet gotten enough heavy equipment ashore to defend against this type of attack. Many hundreds of Marines were killed or wounded. The survivors were bogged down with the little cover they could find. The beach became a graveyard of dead Marines and a salvage yard of wrecked trucks and jeeps. One Marine on the beach summed it up as he told his fellow soldiers, “this is a fucking slaughter.” Those would be his last words, as he was hit with a mortar shell moments later.

Many clergy and priests charged onto Iwo Jima with the Marines. Father Paul Bradley, the priest who had married John and Lena, was one of them. He had volunteered for a combat assignment, saying that a combat area was a place where a priest should be. He was there at Iwo Jima on Day One to provide comfort and administer “last rites” to the dying men. He told his story in the book Flags of our Fathers. He said “I was young and didn’t think about the danger to me. And I was too busy crawling from dying man to dying man. It was always, ‘Father over here!’ Once I was kneeling in the sand administering to a guy who had been hit. There was a loud thud! His eyes closed, he had been hit again, and was now dead. ‘Father over here’, I heard someone else call. I went on to the next one.”

John Gets the Attack Started

The troops had trained for years, but nothing could prepare them for what was happening all around them. The soldiers would later say how frustrated they were that they could not see the enemy to fight back. The Japanese counterattack had stalled the U.S. invasion. Most Marines were hiding in the sand. The beach was littered with damaged vehicles, equipment, and dead soldiers. Further landings of more men and equipment was put on hold. The invasion was not moving. Brave men with leadership ability were needed to rally the troops. One of these men was John Basilone. Many survivors of the battle recall that in the midst of the battle, with everyone hunkered down in the sand, there was one Marine out in the open, running around, directing men. It was John Basilone. He first guided a tank out of a mine field. Only a few tanks came a shore and they were needed to knock out Japanese blockhouses.

Charles Tatum describes John Basilone’s action in his book Red Blood, Black Sand. “I noticed a lone Marine walking back and forth on the shore, among hundreds of prone figures, kicking asses, shouting cuss words and demanding, Move Out! Get Your Butts Off the Beach. He gave the Marine Corp signal to follow him. A group of men responded. Fascinated, I wondered why he wasn’t digging in like the rest of us. As he advanced, I recognized the solitary Marine was John Basilone.”

John had noticed a particular Japanese bunker had been effectively shooting mortar shells and raging deadly fire upon the U.S. troops. This enemy strong position “had to go”. John found and organized some machine gunners along with demolition men and directed them toward the bunker. First, the Marines fired on the bunker causing the Japanese to take a defensive position and close the gun port. Then the soldiers advanced toward the bunker. John Basilone instructed a demolition man to blow a hole in the concrete structure, while others gave cover against other nearby enemy positions. The demo-man charged the bunker and quickly tossed his explosives at the base of the closed metal door and ran for his life. A large explosion went off opening part of the bunker. Basilone then told the enthused machine gunners to hold their fire and directed a flamethrower operator to charge the pit. The flame throwing unit, worn on a soldier’s back, weighed seventy pounds. The brave flamethrower charged the pit as quickly as he could, stuck his nozzle in the pit and ignited the flame. This flame was an effective weapon. It contained napalm, which leaves a burning gel on those that it touches. Some of the Japanese soldiers ran out of the pit screaming as they tried to wipe away the jellied gasoline that was burning them. John Basilone cut them down with a machine gun.

Fellow soldier Charles Tatum, who held the ammunition belt for John Basilone recalls “Basilone’s eyes had a fury I had never seen before. Rigid hard clinched jaw, sweat glistening on his forehead; he was not an executioner, but a soldier performing his duty. For me and others … who saw Basilone’s leadership and courage during our assault, his example was overwhelming.”

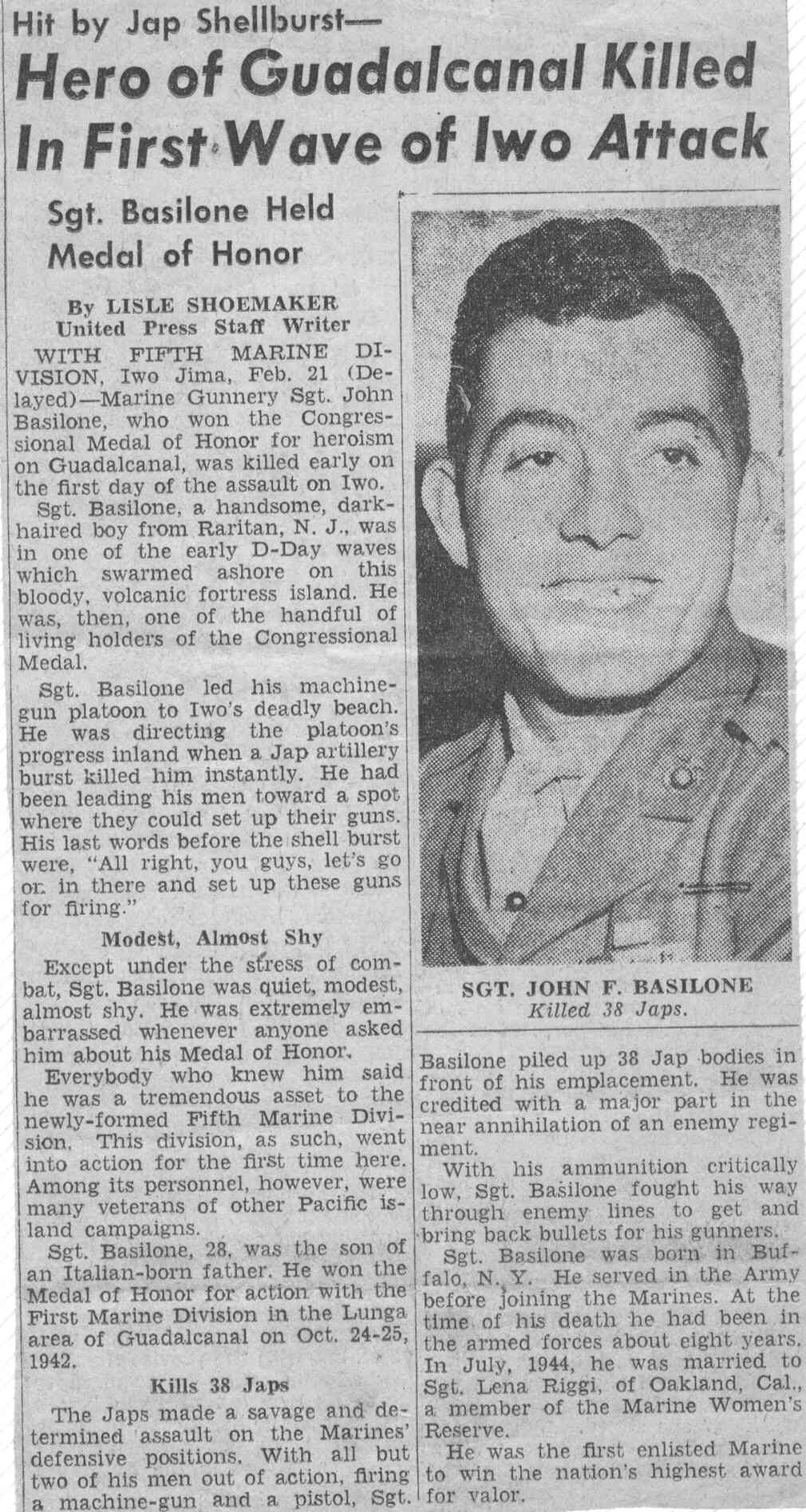

The Death of Manila John

After knocking out the bunker, Basilone led twenty men off the exposed beach area to a location where they could take some cover and plan their next move. They were inside a crater that appeared to be made earlier by a U.S. bomb. John Basilone judged that they would need more men to advance against the next Japanese blockhouse. He ordered the men to stay while he went back to get more men and some heavy machine guns. The young soldiers waited and watched Basilone run back to gather more men. John Basilone gathered some troops and weapons and started back across the beach to the waiting soldiers. A Japanese mortar shell landed right in the middle of John and a few of the men he was leading. John’s reported last words, just before the shell hit him were printed in The New York Times, they were “All right, you guys, let’s go on in there and set up these guns for firing”. The shell killed several men next to John instantly, but John, held on. One soldier who witnessed his injury described it as very bad. The explosion had ripped his insides open and part of his intestines were exposed. John held his hands on his stomach as blood oozed all around him. A small puddle of blood formed and started to grow slowly. A medic was summoned. John Basilone’s only chance was if the medics could get him off the beach to a hospital ship. However, at the moment, there were no more ships coming in or going out. The beach was in chaos. There was a log jam of ships, wreckage, and bodies. No more ships would be landing until the U.S. was more organized and the incoming ships were not sitting ducks. The medic shot John with morphine to comfort him. At one point some men stopped to gaze at the fallen hero, but a sergeant yelled them off, not wanting to see them get shot while grieving for him. John clung to life for around thirty minutes before dying.

Word started to circulate among the Marines that John Basilone had been killed. Several men recalled that this rallied the Marines. Before they were hunkered down, afraid to advance, but now they rose and charged the Japanese positions with renewed energy. They took casualties, but started to complete their objectives, foot by foot, blockhouse by blockhouse.

One soldier, Adolph Brusa, who witnessed John’s action that day, said in an interview for the video The Saga of Manila John, “John Basilone was killed at Iwo Jima because he was a God Damn Hero. While everyone was hugging the ground, he was out there leading the men.”

John’s “back pack”, which he discarded during the battle at Iwo Jima, was found in the sand by Tony Cirello, a soldier who also came from Raritan. He would later give it to George Basilone.

The Basilone Family and Raritan Learns of John’s Death

News of John’s death, which had occurred on February 19th, 1945, did not reach home until March 8th, 1945, a Thursday. The military’s standard procedure is to notify the family before the media. However, in John’s case, something got mixed up. The first notification of John’s death came to the family when a reporter, on the morning of March 8th, got in touch with John’s brother Angelo’s wife, who lived on Second Avenue in Raritan. She quickly went over to the family home at 113 First Avenue to ask John’s mother Dora if it was true. Dora had not yet received any information, so they clung to hope that the reporter was in error. However, ten minutes later, a Western Union telegram from the War Department was delivered to John’s father Salvatore at his new job at Holcombe and Holcombe on West Main Street in Somerville. (He had recently sold his tailor shop.) It read:

Deeply regret to inform you that your son, Gunnery Sgt.

John Basilone, USMC, was killed in action February 19th at

Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, in the performance of his duty

and service to his country. When information is received

regarding burial, you will be notified. Please accept my

heartfelt sympathy.

General Alexander Vandegrift

A similar telegram was sent to John’s wife Lena, who was stationed at Camp Pendleton in California.

John’s father quickly called home and delivered the tragic news. Dora was in a state of stock and described as being on the verge of collapse. Salvatore quickly came home and soon word of John’s death spread throughout the town. When a local Raritan boy died in the war, the word always spread quickly. Police Chief Lorenzo Rossi went around town informing people of John’s death. The station master at the Raritan Train Station told commuters as they walked to the train. The church bells at St. Ann’s were rung.

Father Amedeo Russo of St. Ann’s soon arrived at the house to comfort the family. The Basilone house was quickly flooded with visitors offering their sympathy.

John’s sister Dolores described for this book how she was notified. She was in class at Somerville High School when the principal of the school came in and said that her dad had called. She, along with her younger brother Donald, had to go home. No other information was given to them, but when the principal himself drove them both home, they started to realize that something major had happened. They were informed of John’s death when they arrived home.

Back then, the two local papers, The Somerset Messenger Gazette and The Plainfield-Courier News, were printed and distributed in the afternoon, so they were able to report the story the same day. It was the lead story on the front page of both papers.

The last word that the Basilone family had received from John was a birthday greeting to his mother, one month before. The Basilone family and the town of Raritan grieved over the loss of their hero.

Judge George Allgair was quoted in The Somerset Messenger Gazette “The boys in Raritan all idolized John Basilone and his death seems unreal. We have a very deep sense of loss.”

Former (Municipality) Mayor Joseph Navatto commented on a talk he had with John on his last home visit, “he said he couldn’t take it easy while his friends fought on. He had to get back to the fight. If his number came up, that was part of the game. He was a tribute to this great country of ours, an American, a Marine, a hero who gave his life for the country he loved.”

Father Amedeo Russo of St. Ann’s said in The Plainfield Courier News, “John Basilone had a high sense of patriotic duty, which impelled him to give all in his service to his country. He has left a noble example of unselfish devotion to duty.”

The New York Times wrote about John, “Being a Marine fighting man, and therefore a realist, Sergeant Basilone must have known in his heart that his luck could not last forever. Yet he chose to return to battle.”