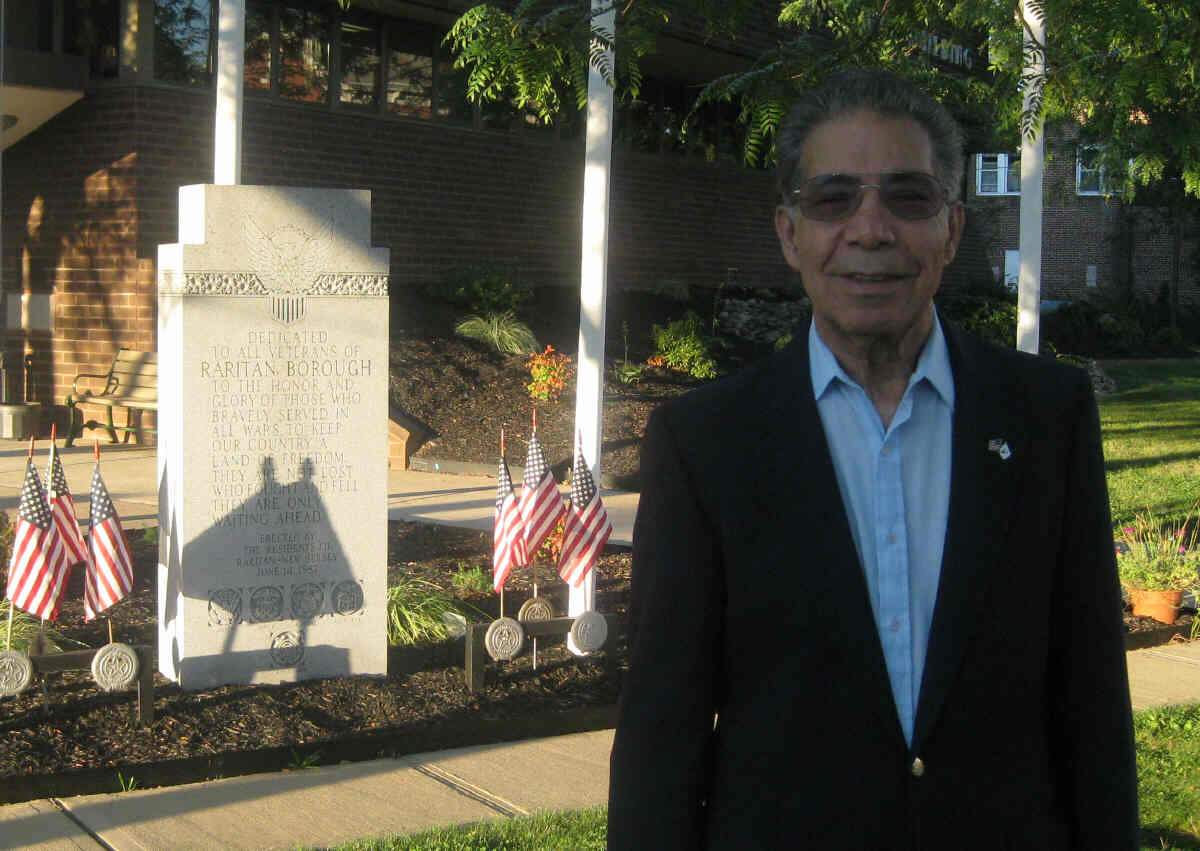

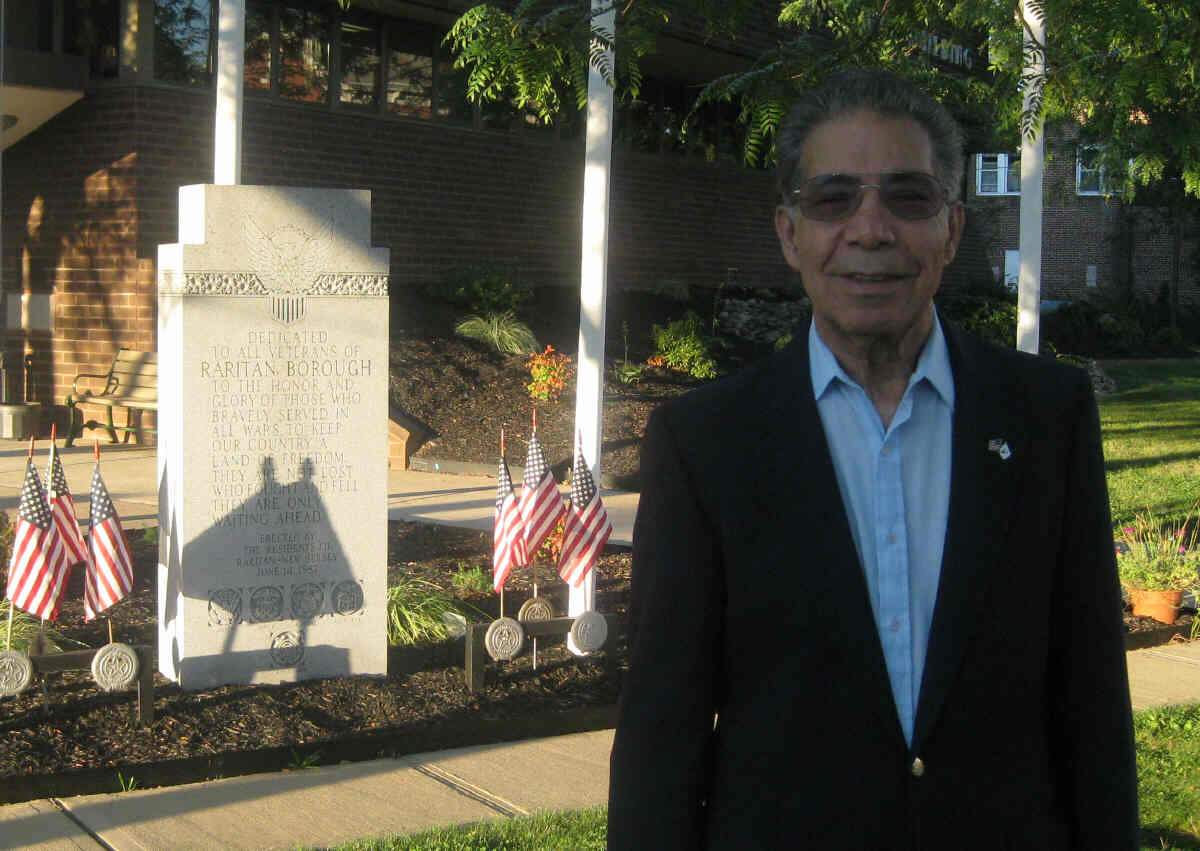

| John Lamaestra is the Grand Marshall of the 2013 Basilone Parade |

|

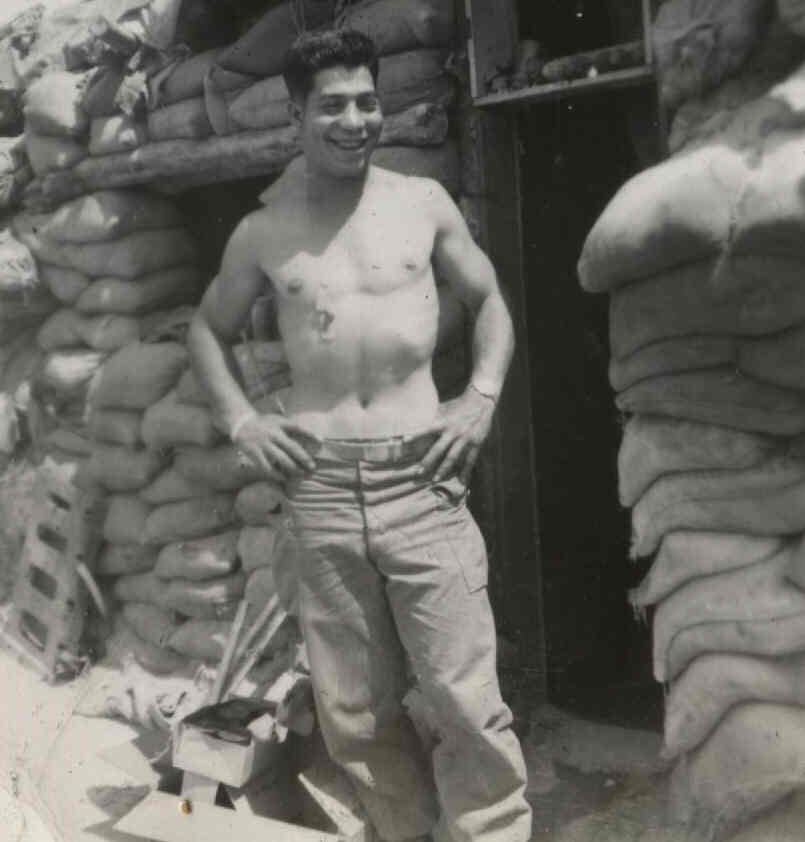

This author was pleased to have the opportunity to talk with former Raritan councilman John Lamaestra about his experiences

in the Korean War. Years ago while John was on the Borough Council I asked him a couple of times if I could write an article about his time in Korea.

But the modest veteran always declined as he did not want to use his service to his country as a vehicle to gather votes.

Now retired from politics -

and serving as The Grand Marshall of the Basilone Parade - he sat down with me and related his war time and lifetime experiences. |

|

Born in 1930, John Lamaestra grew up during the depression in Brooklyn. He was the 13th of 14 children. His parents, Rose and Basilio,

had been born in Italy but immigrated to the U.S. where they met. Each parent was married before but their spouse had passed away.

When they got married,

Rose already had four children and Basilio had one. Together they would have nine additional children. |

| John is on the left, third from bottom. |

|

Times were tough when John was growing up,. They had a large family to feed and at times his dad, like many others in this country,

was out of work. But all the older kids worked when they could and pooled their money together to put food on the table. Even six year old John knew it

was important that he help his family. He made a box to hold shoe shining equipment and he hustled on the street corners of Brooklyn yelling “Nickel Shine –

Nickel Shine”. He appreciated every nickel he made. Occasionally a well to do businessman - admiring the thrifty six year old - would pay him a dime –

and that would make his day. There were other jobs that he did too. Neighbors, knew young John was looking for work and would send him to the grocery

store to pick up a few items. The usual tip for that service was two cents. The pennies that he earned were given to his mom to add to the family food fund.

Sometimes his mom gave him back a penny and told him to get himself a piece of candy from the corner store – which he immediately did. |

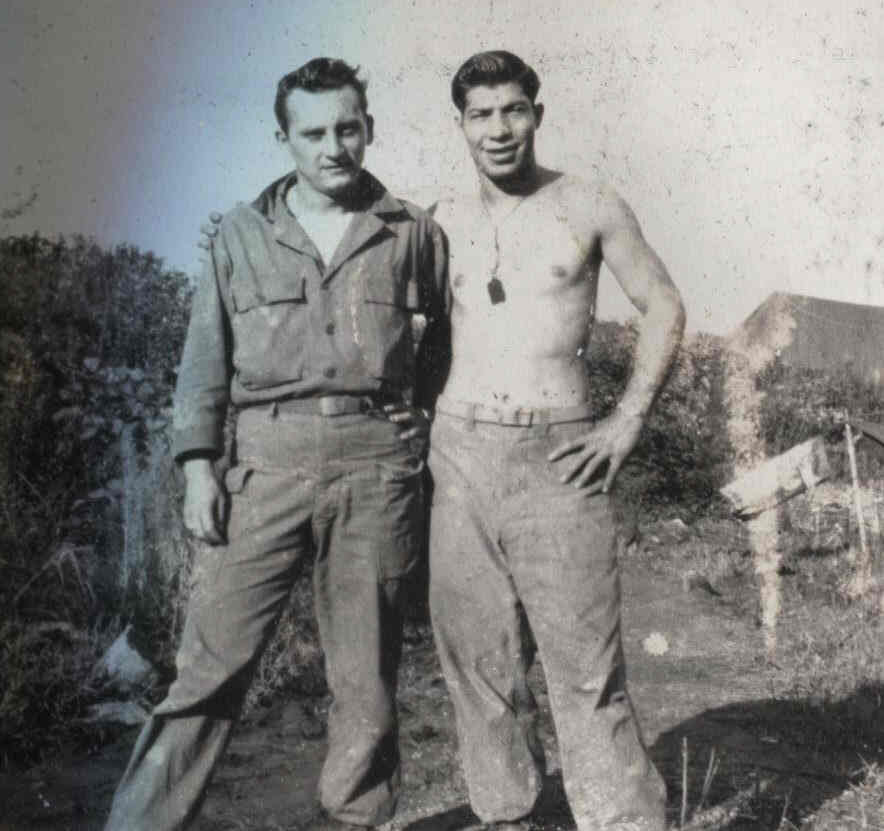

The above painting was done while John was in the army.

Ironically the portrait was the grand prize in a BINGO game. |

|

The affording of food was such a concern for the family that John still remembers the price of a loaf of bread. A local baker had a deal if you bought nine loafs at seven cents each you would get three free. Any deals for food in these tough times were taken advantage of. The images of his old Brooklyn neighborhood are still firmly etched in John’s memory as today he still remembers the street in detail - who lived where – the location of the stores - and where the kid’s makeshift ball fields were. |

|

When he was ten years old his family moved to South Bound Brook. He would attend Bound Brook High School graduating in 1949. He then went to work for Bakelite in Piscataway. When the Korean War started, John wanted to follow a family tradition and volunteer to serve, as six of his brothers served in World War II, but he held off since he was still living at home taking care of his now aging mom. Eventually the draft called him in 1951 and he reported to the Army. |

|

After state side training, he arrived in Korea in June of 1952. The officers wasted no time preparing and putting them into battle. The first day John was assigned to a unit that would soon be attacking a hill that was heavily defended by the enemy. They named the upcoming offensive “Operation Boland”. Around a hundred men would be in the battle. They began training immediately to charge up a hill and attack an entrenched enemy. For six days they trained – they kept doing the same thing over and over. The morning arrived for the offensive – and they moved toward the hill. Before the ground troops engaged, the U.S. artillery shelled the North Korean positions. This shelling was so accurate (and effective) that the commander said to keep the shelling going even while the ground troops crept in close. When the artillery barrage was complete, the ground troops began their attack. The North Koreans fired back phosphorous shells, but they were in a panic and many of these landed on their own troops. As the attack developed John said “the (shoulder held) bazookas were invaluable” as they knocked out enemy positions. John’s platoon came in toward the end of the operation. In our interview John made it clear that while he participated in this battle, the first guys in were the heroes, especially those who were killed or wounded. He said “All those guys deserve a medal”. It was only after that first battle that John learned what unit he was in. He was in Fox Company, 32nd Infantry Regt. 7th division. |

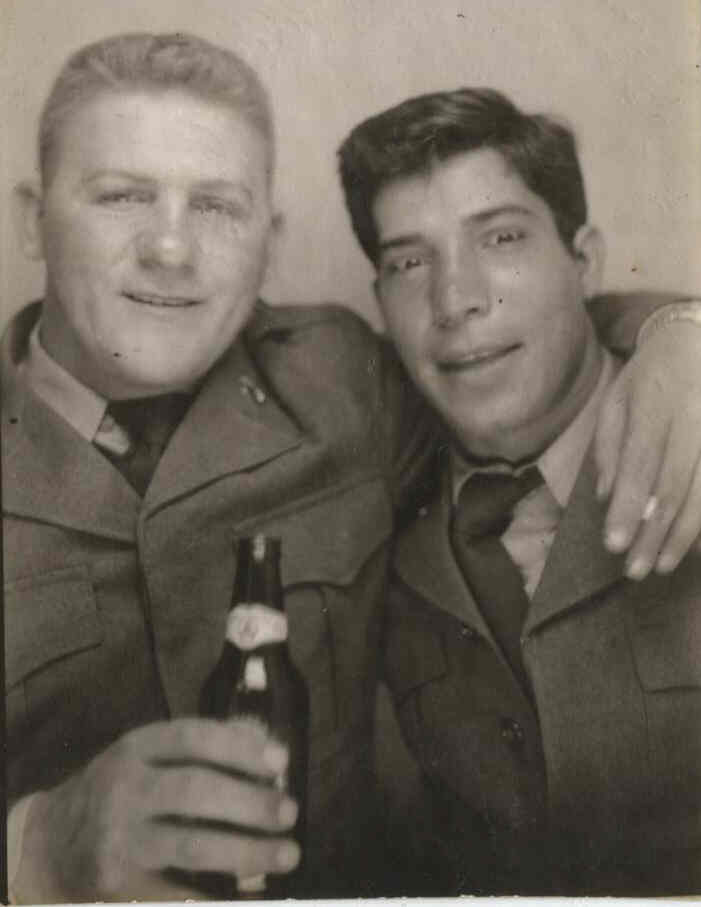

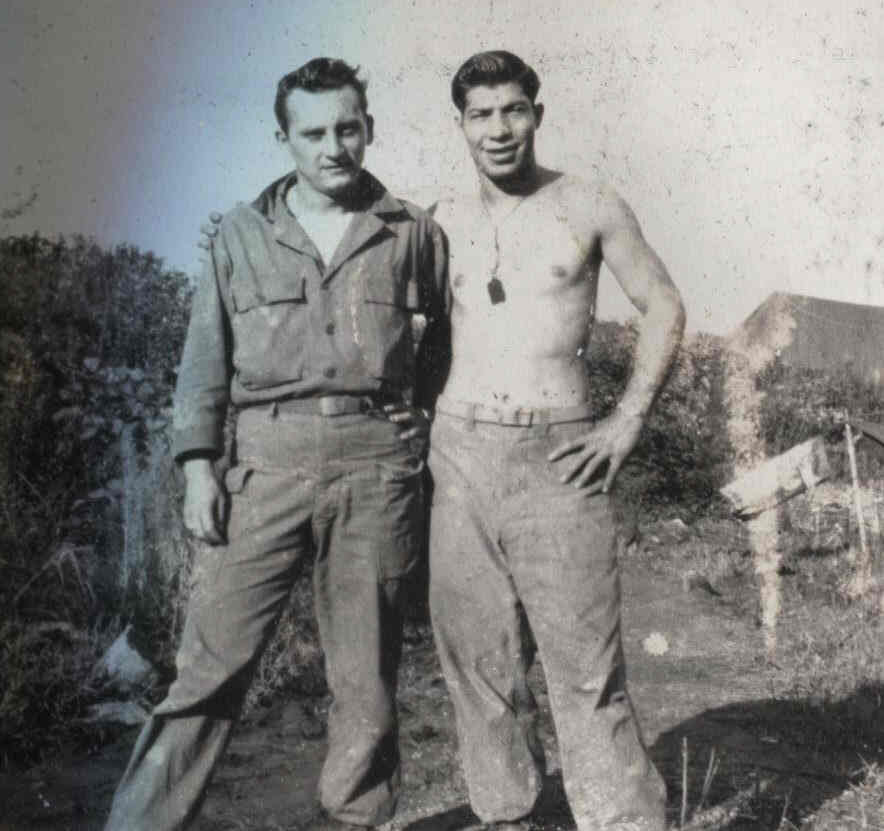

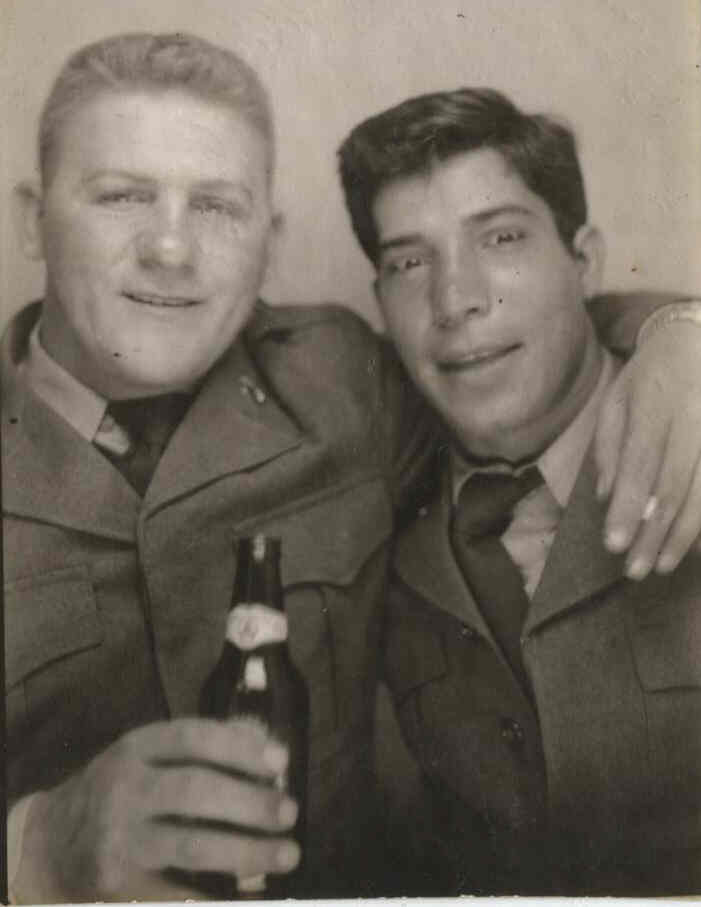

| John is on the bottom left. |

Click to see battle report from "Operation Boland" |

|

“Operation Boland” was a “hit and run” operation whose objective was to inflict damage on the enemy. That objective was achieved

as the North Koreans had over 50 men killed while the U.S had just 4 killed and 8 injured. The battle was small by the standards of the Korean War.

Thus for half a century the battle was forgotten. John had commented in our interview that he had searched a few years ago on the internet for “Operation Boland”,

but found nothing. After our meeting this author did an internet search and surprisingly learned that “Operation Boland” reemerged in the news two years ago when

President Barack Obama awarded the Medal of Honor (MOH) posthumously to a soldier in that battle - Henry Svehla. The Medal of Honor Ceremony was held in the White House on May 2nd, 2011 - 59 years after the battle - with Henry’s sisters in attendance. Henry had led his unit in the first parts of the battle – and toward the end of the battle he threw himself on a grenade that had landed in front of him and several fellow soldiers. The blast from the grenade resulted in his death, but saved several other soldiers in his unit. |

Fellow Soldier Henry Svehla was awarded the

Medal of Honor posthumously in "Operation Boland" |

|

When this author asked John Lamaestra if he knew of Henry’s heroics and the recent awarding of the MOH he responded that while he

recalled his heroics, he was not aware of the recent awarding of the Medal of Honor. Back in 1952 the surviving soldiers had thought that Henry should be awarded

the Medal of Honor for his sacrifice. Ironically, John had even written home from Korea about this. He still has a letter he wrote to his girlfriend Gloria

(now his wife) after the battle. John wrote that during a recent battle a soldier threw himself on a grenade to save his buddies. He went on to say that the

fallen soldier should receive the Medal of Honor. John was right about the awarding of the MOH, but who would have thought that it would take almost 60 years

for it to happen. |

President Obama presents

Henry Svehla's Medal of Honor to his sister. |

Click to see letter John wrote home to his girlfriend Gloria |

|

At “Operation Boland” and in a couple of other battles John Lamaestra saw the horrors of war. When this author asked him about it he said “It is not a thing to talk about. I still dream about it. It comes back to you. You never forget it. “

There were many other dangerous times in Korea. He was often sent out on reconnaissance patrol. He along with a small group would venture out a mile or so from their position to listen and observe. They were armed but they were told if possible not to do battle with the enemy. It was information that their commanders needed not one or two dead enemy soldiers. These reconnaissance patrols were still dangerous as the enemy could be waiting to ambush them. Occasionally their patrol would stumble into another U.S. patrol. Sometimes a shot would be fired before they realized that the shadows they saw in the dark were friendly forces. On John’s patrols there had been a couple of shots fired, but fortunately no one was killed by their own forces.

|

|

|

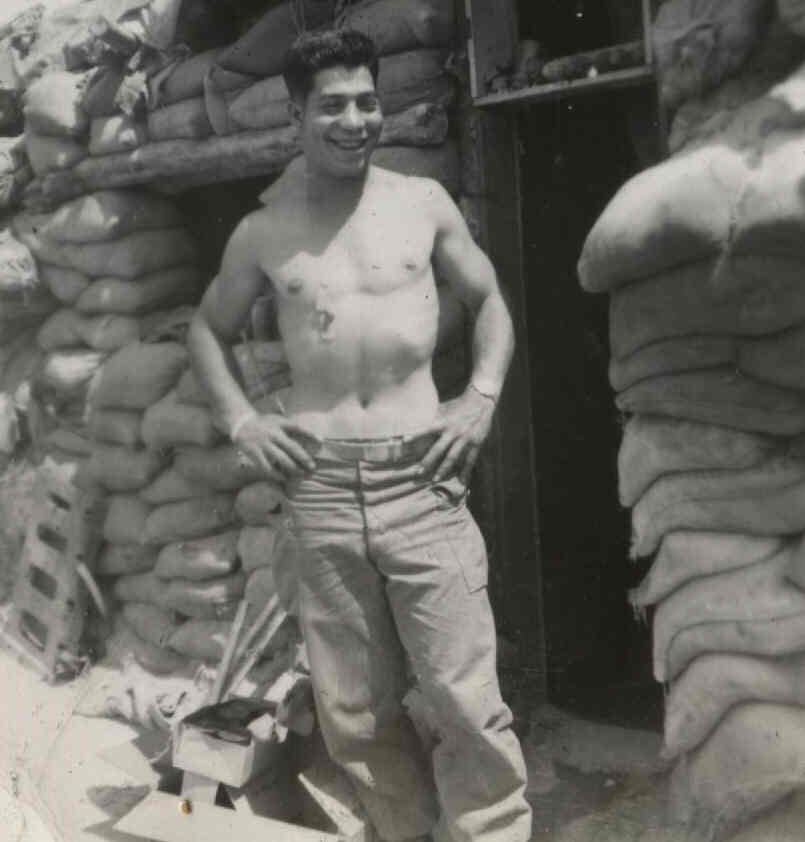

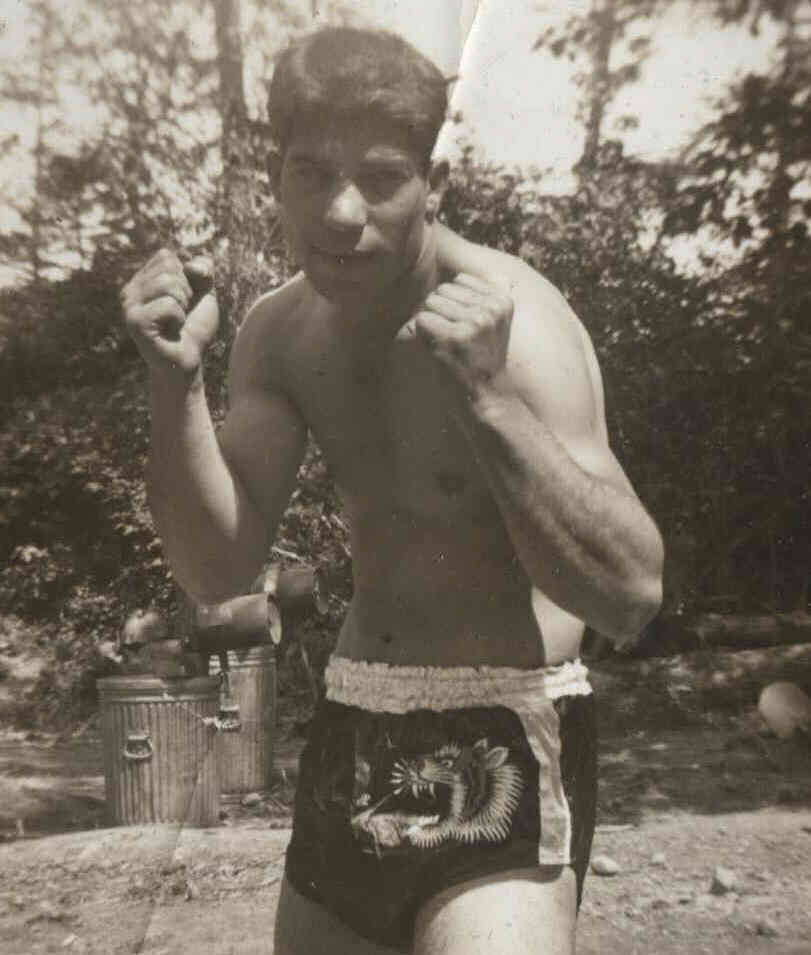

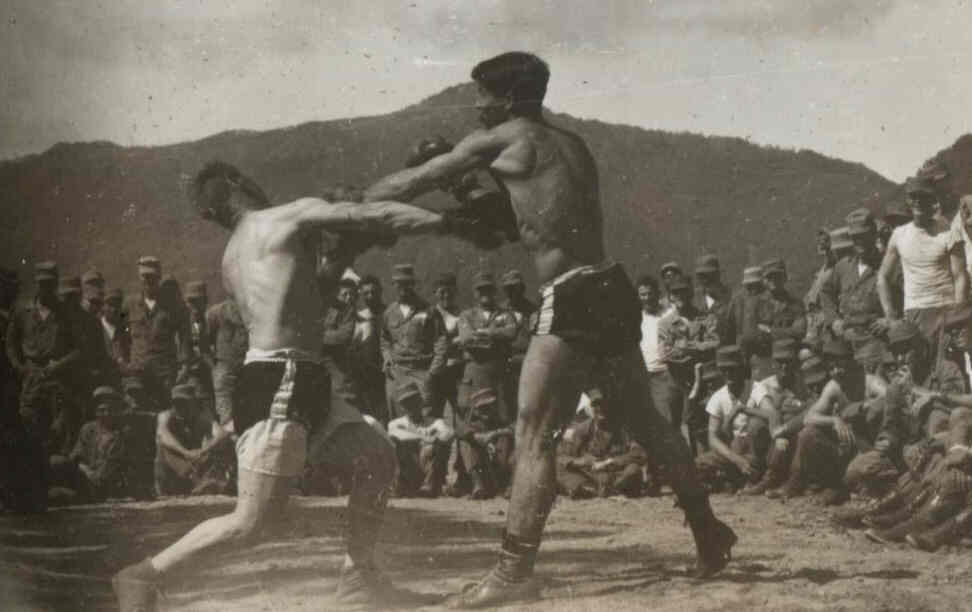

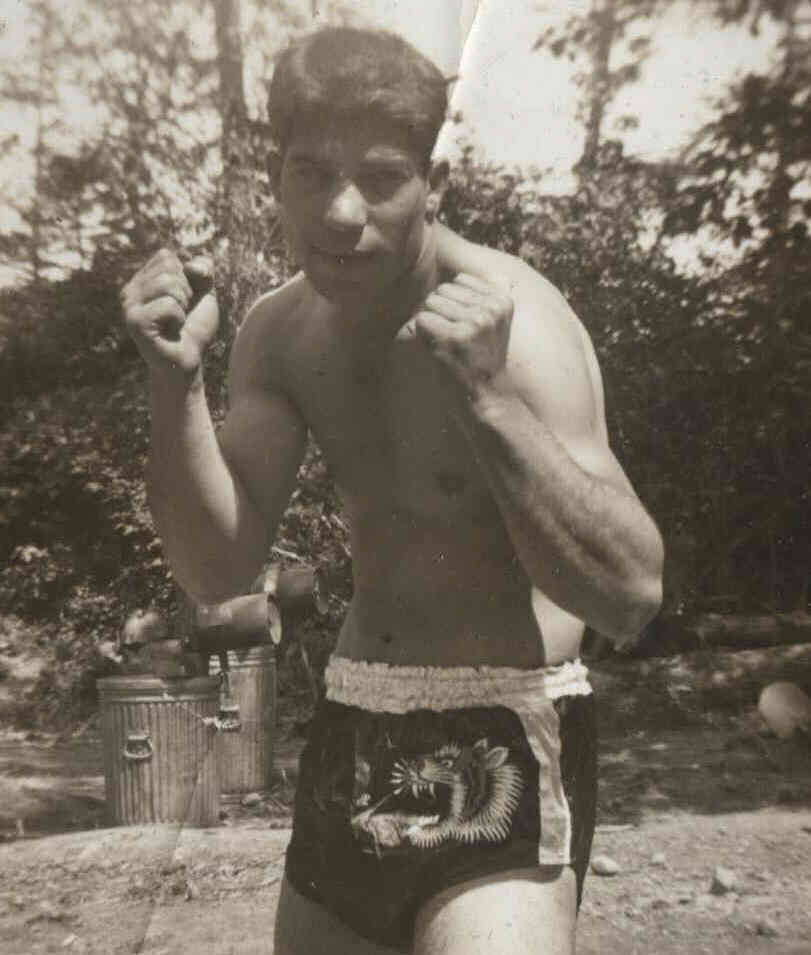

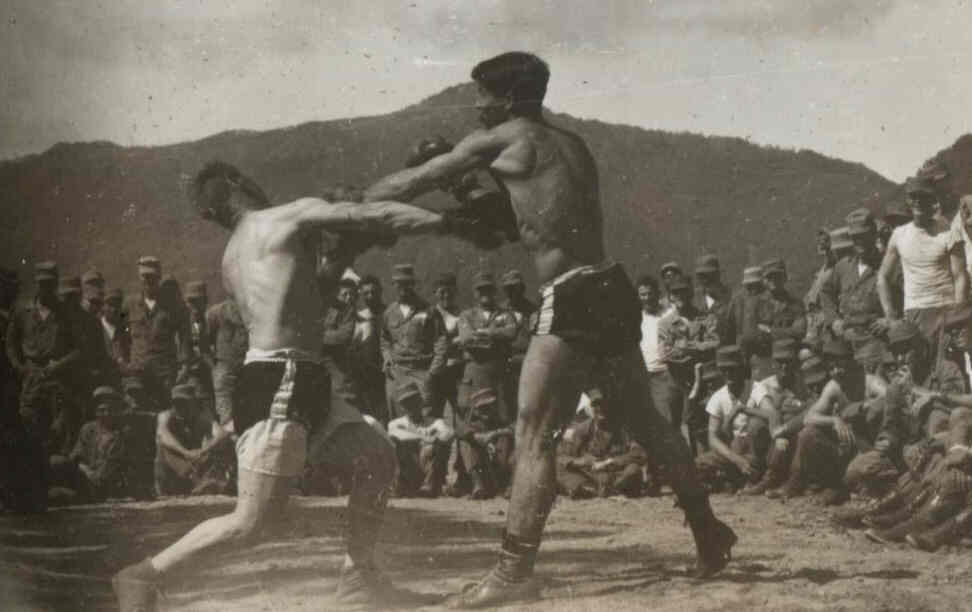

| John boxed in the army. On the right, Lamaestra delivers a nice jab |

|

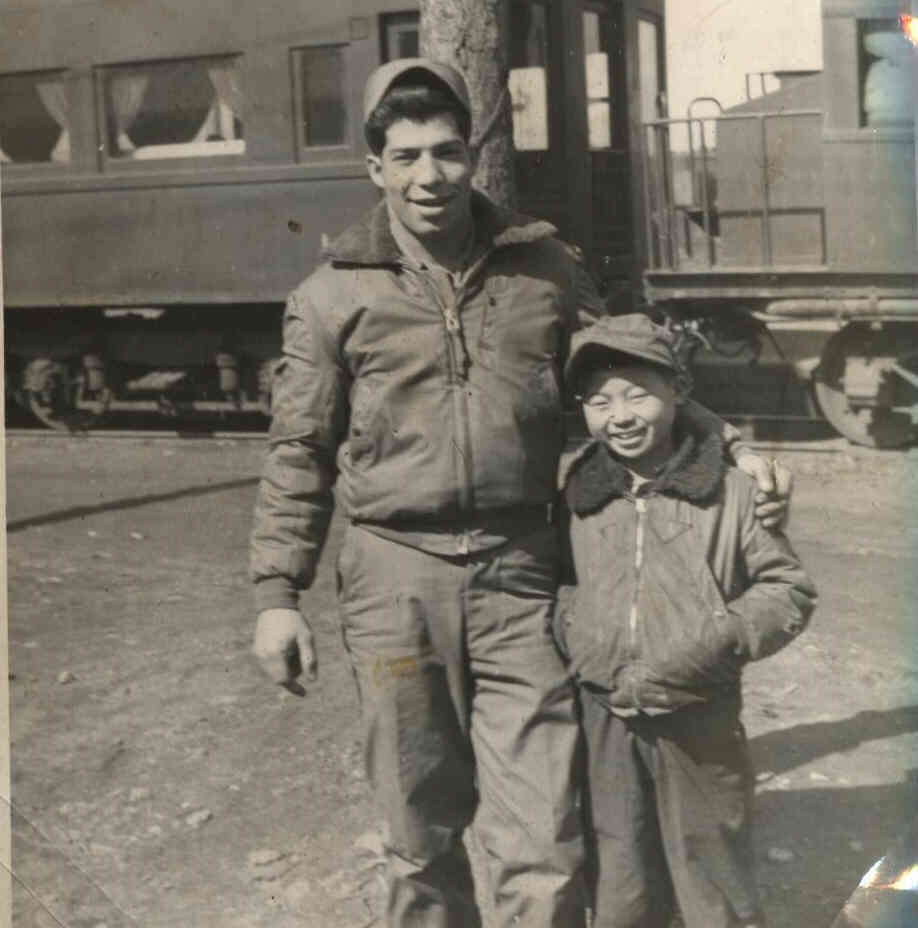

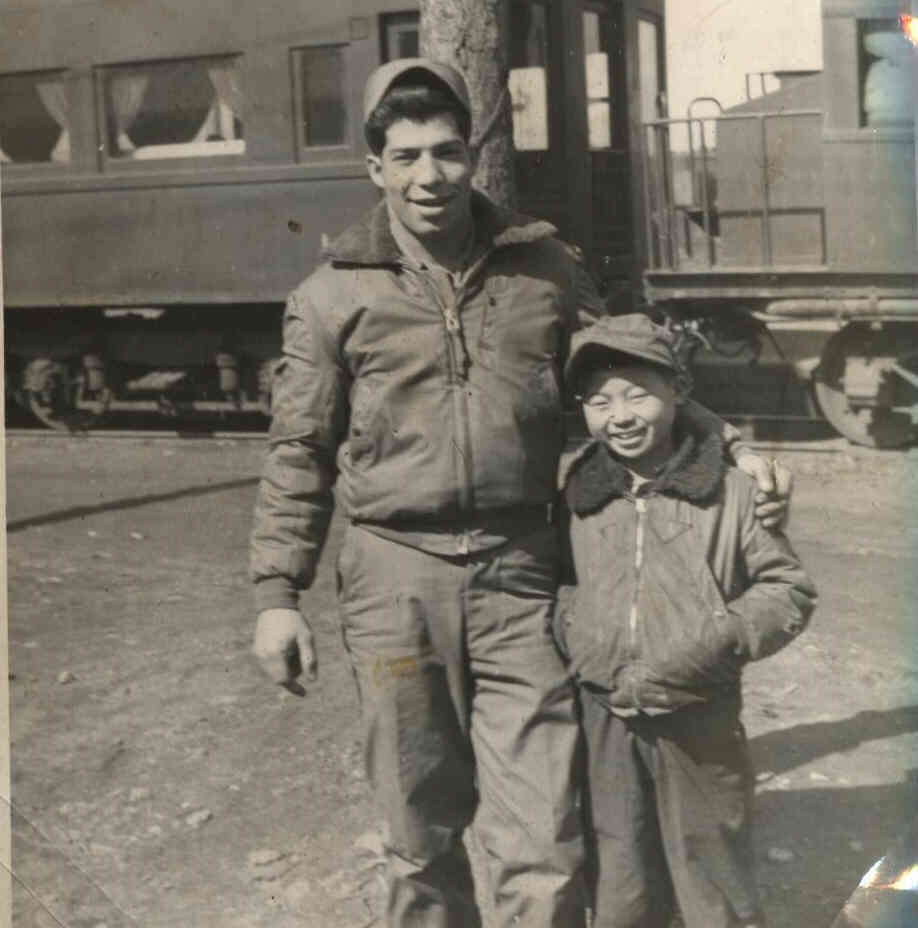

In the last few months of John’s service in Korea - while stationed in Daegu, South Korea - he became good friends with a ten year

old Korea boy named Joey. He recalled that he took a liking to the kid right away – and the kid liked him right away too. Joey always came around to hang out with John.

John said Joey was like a son to him. John even bought Joey an army uniform and hat just like what he wore. Toward the end of his service in Korea John received

his orders to leave Daegu and return home. He said a sad goodbye to Joey. Even today John said with a heavy heart “Joey cried like hell when I left”.

John gave Joey his address in the U.S., but he unfortunately never heard from him.

John did not know Joey’s last name so tracking him down today would be very difficult.

It would be like finding a needle in a haystack – a faraway haystack at that. But a good clear photograph of John and Joey together survives to this day.

So this author has decided to make an attempt to find Joey. There is still a U.S. military base in Daegu today so we emailed the photo with our story to their

public relations department asking if they could possibly point us in the direction of a Newspaper / News agency in the Daegu area that might print the photo

asking if anyone recognizes Joey and knows his whereabouts. They emailed us back and said they would try to help us |

John said Joey was like a son to him

Click to see full photo |

|

John Lamaestra would return from Korea in November of 1953. He went back to work at Bakelite where he would stay another 40

years before retiring. In 1955 he would marry his longtime girlfriend Gloria who lived in Raritan. They moved into her home at 32 First Avenue –

they still live there today. They would have three children – John, Darryl, and Scott.

Over the years John Lamaestra has been involved in various

local organizations such as the American Legion and the VFW often taking a leadership role. This year he is The Grand Marshall of the Basilone Parade.

|