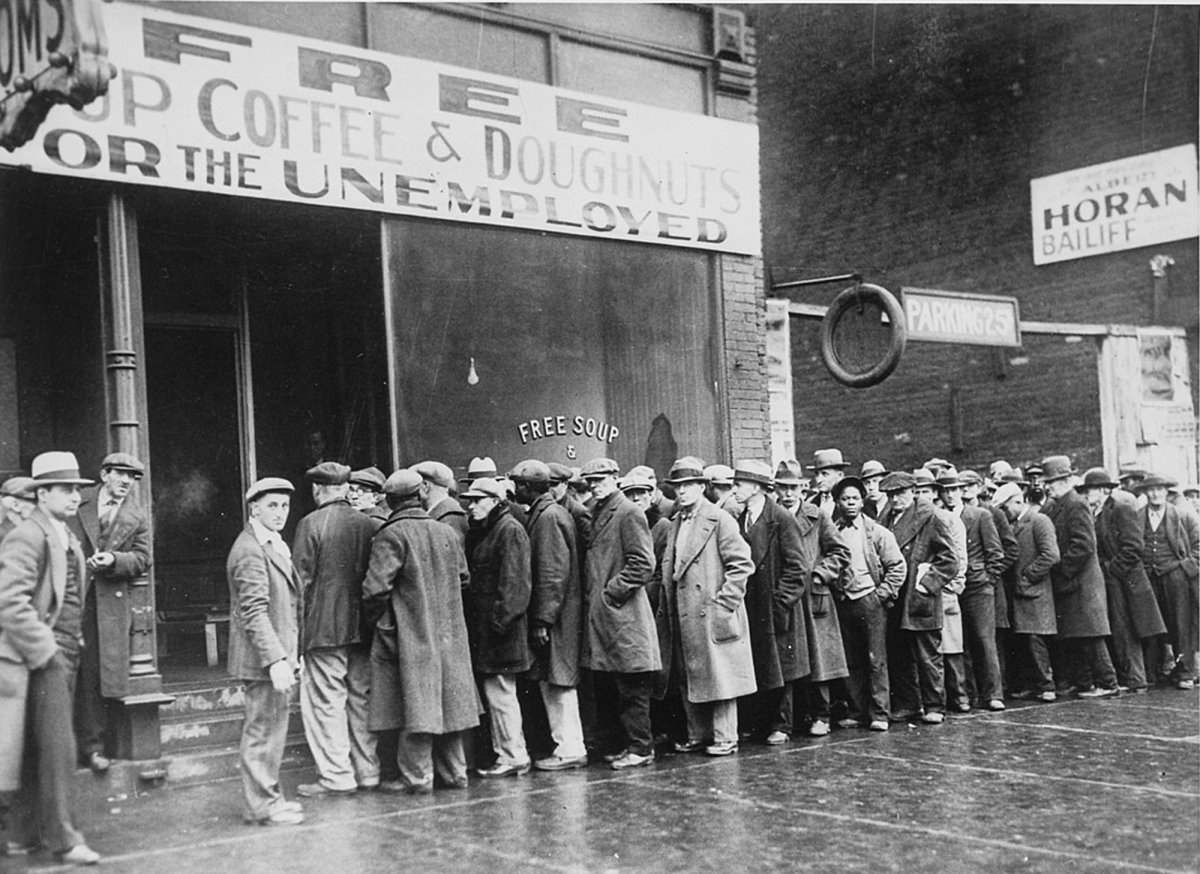

Locally, Raritan and Bridgewater, like all towns, were hit hard economically. Numerous businesses had closed. Even the one movie theatre had shut down. Many families had to rely on generous credit terms from local mom and pop department stores for basics such as shoes.

were common during the depression

But toward the end of the previous year the Supreme Court of the United States had struck down several pieces of his legislation declaring them unconstitutional.

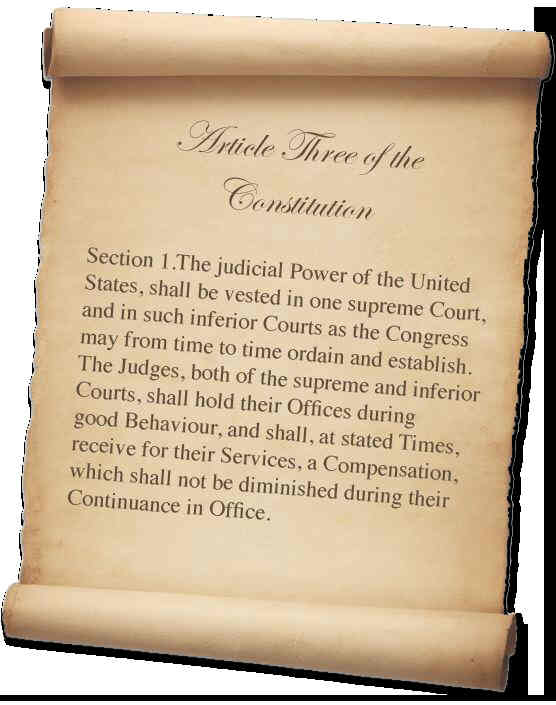

This type of court was a novel idea (part of a new experimental type of government.) Its purpose was to provide vital checks and balances on the other two branches of government - the legislative (Congress), and the executive (the President).

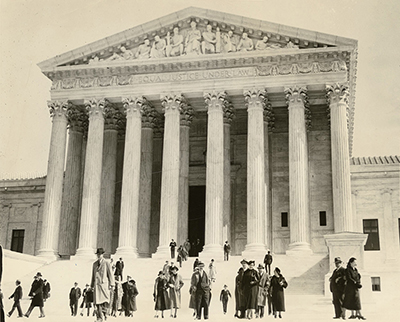

Initially no one was sure what to make of this Court, but over the decades the level of its power and respect grew substantially.

As time went by it was felt that a branch of government as important as the Supreme Court should have a building that was representative of its prominence. In 1935, the beautiful Supreme Court Building that we know today with its marble columns was complete. Both the outside and inside are a marvel to view.

Now FDR is rightfully ranked by historians as a great President who led us out of the depression and later to victory in World War II.

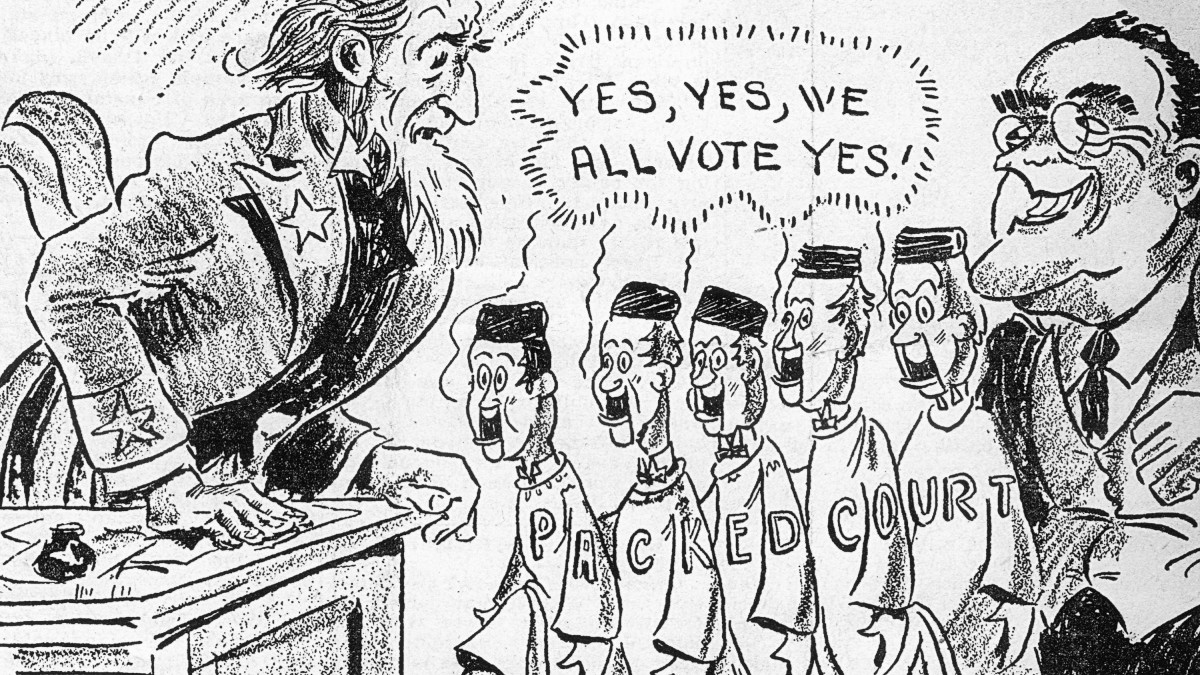

But here, due to his blind determination, he wanted to find a way around the veto power of the Supreme Court. He schemed and came up with an idea for how he could get the Court to rule in his favor.

opposed the court packing plan.

Click to view more.

FDR knew that our Constitution stated that the Supreme Court Justices were appointed for life. This was done to ensure that the justices were truly independent of any political pressure that could result from an upcoming election or re-appointment.

But the number of justices according to the Constitution was determined by the Senate. This number had varied over the years starting with five in 1789, but had been set at nine since the Judicial Act of 1869.

The President thought with new judges that a previous 5-4 vote against him would now go for him as he would appoint judges who he felt would rule in his favor. All that FDR needed was Senate approval.

second inauguration in January 1937.

His stated reasoning was that the Court needed new blood and that the Court was behind on its work. Congress, the public, and the press were shocked. It was labeled FDRs court packing plan.

The members of his party weighed their allegiance to FDR against the Constitution of the United States, which is the foundation of our Country. An initial mixed reaction slowly turned to condemnation.

The Supreme Court has served a useful purpose. Its value would be destroyed ... if every President were determined to bend it to his wishes. We doubt if the American people are willing to sit by while one of its cherished institutions is destroyed by the impatience of its leader.

One Senator, a usual supporter of the President, said A cause was never won by stacking a deck of cards, by stuffing a ballot box, or by packing a court.

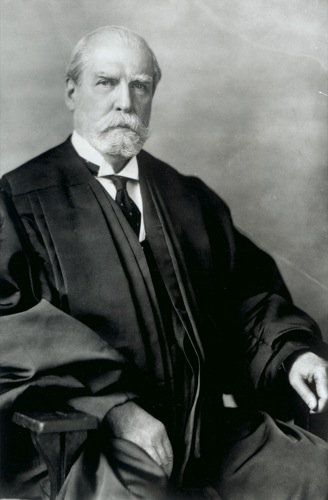

Supreme Court Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, breaking with the usual tradition of judges seldom making public statements, spoke out against the proposal. His basic summary was that it would destroy the Court as an institution. He gave evidence that the Court was not behind on its caseload as FDR had claimed.

Charles Evans Hughes

The court packing proposal was first voted down in a Senate committee and even a later compromise proposal that made it to a full Senate floor vote was soundly defeated. The lesson of history here is that back in 1937, Congress chose to respect and uphold the constitutional principles of the separation of powers with an independent judiciary rather than side with a President from their own party.